Marco Galardini

23 August 2023

Even though the lab is focused on bacterial pathogens, we (Marco and Gabriel)

took a look at the “2020 main character” pathogen, SARS-CoV-2, and just

put out a preprint on the topic of real-time identification of epistatic

interactions.

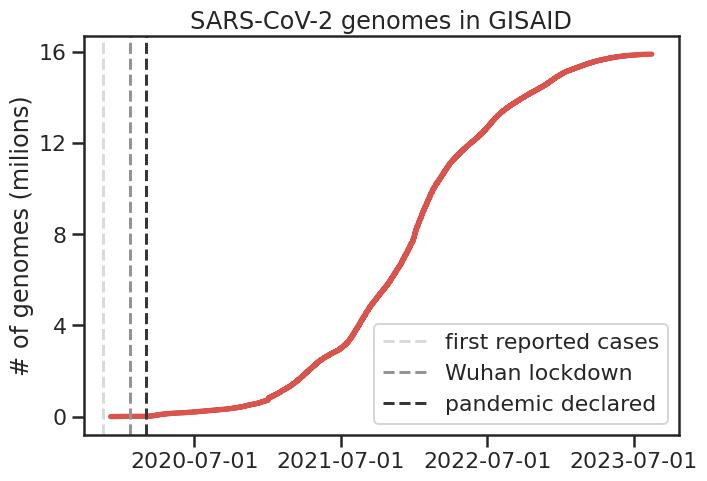

A particularly interesting development during the pandemic has been the

unprecedented amount of genome sequencing, and its use in very quickly

developing diagnostics (e.g. PCR primers) and treatments (i.e. sequence-based

vaccines and their updates).

Other applications closer to our field of study are the identification of

virus variants with a fitness advantage

and predicting the impact of genetic variants on genes and viral fitness.

We asked ourselves: can we find another use for this genomic data?

The application we were looking for would ideally be computed quickly, so that

it could be part of the public health decision process, and should leverage

the metadata associated with each sequence so that context would be taken into account.

We decided to look at a generally overlooked aspect in the evolution of this virus:

epistatic interactions. Generally speaking, two positions in the genome can be said to

interact epistatically if the impact of a double mutation deviates from the “sum” of the

effect of the single ones.

A particularly interesting example of macroscopic epistatic interaction can be found in the history

of scurvy.

We already know that these interactions are important for the evolution of

the Omicron variant (BA.1), has it has been elegantly showed through

experimental work.

These experimental studies are however relatively slow to perform and restricted to

certain regions of the genome (e.g. the Spike RBD). Could we come up with a

fast computational method that scales to millions of sequences?

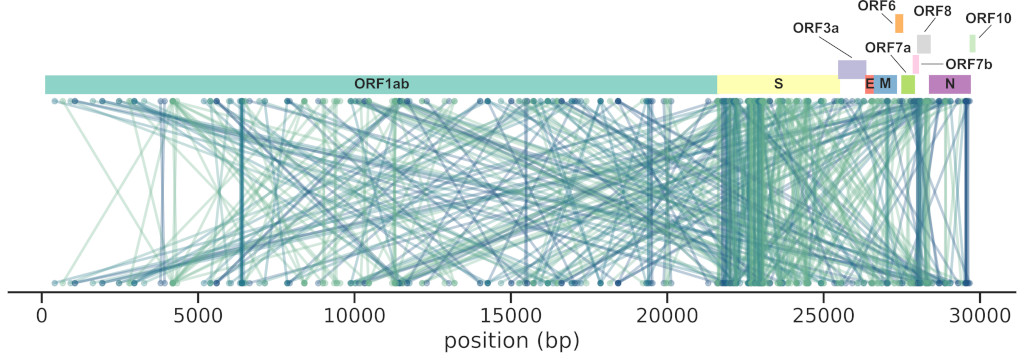

We reworked a method based on mutual information (MI) and applied to a large

set of SARS-CoV-2 sequences (~4M), finding 474 interactions across the genome,

the majority in the Spike gene (185).

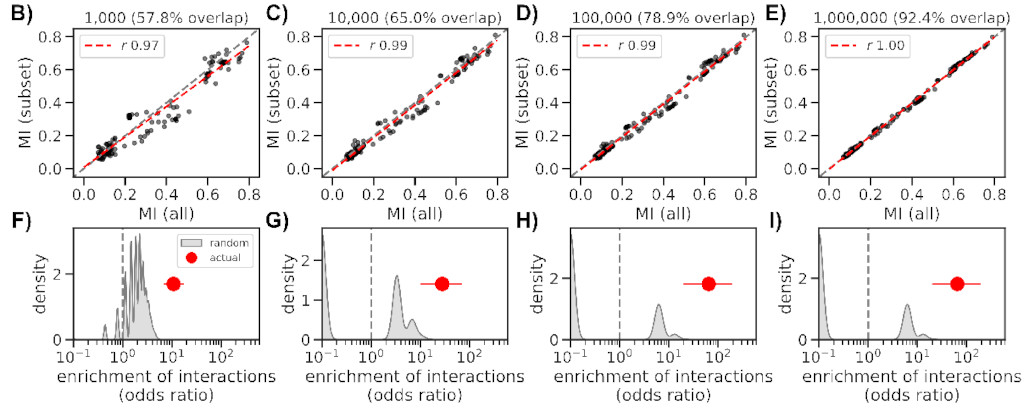

Even though we made the method somewhat scalable, it took ~36 hours to complete

using several nodes on HZI’s cluster. But luckily we can obtain similar results

with as few as 10k sequences (a bit better if closer to 100k), which only takes

2 hours to complete.

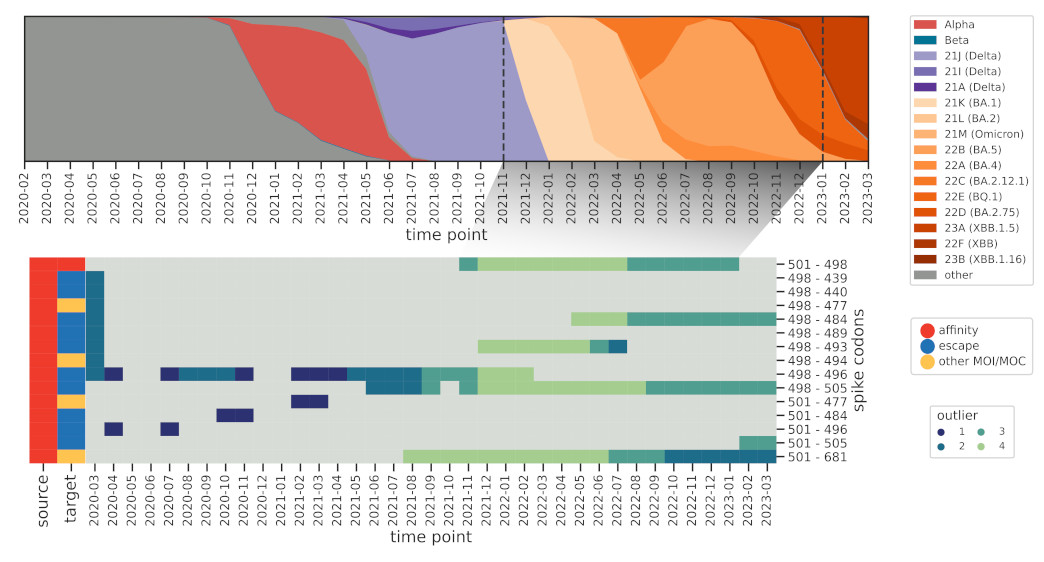

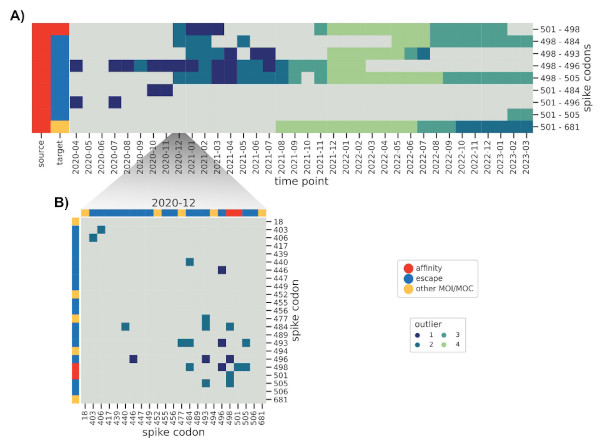

How do these interactions change over time, and how quickly can we spot known ones,

such as those found in Omicron BA.1? We further modified the method to reduce the influence

of older sequences and thus highlight emerging interactions.

And indeed we were able to identify a cornerstone epistatic interaction in the Spike protein

between residue 501 and 498 as early as 6 (!) Omicron sequences were present in the dataset,

which speaks to the sensitivity of the method.

The flip side of this sensitivity is that genomes with incorrect metadata (i.e. date)

will make epistatic interactions appear at odd times, which was the case before we

used the excellent community resources put together by Emma Hodcroft.

We hope this work demonstrates that pathogen genomic sequencing is here to stay,

as the data can be used to generate many useful predictions that can in turn guide

public health decisions.

This work was started during the first lockdown, but it was significantly advanced by

Gabriel Innocenti, who was supported first by a FEMS research and training grant

and then by RESIST. A real pleasure to work with him!

P.S. as with our other papers, we have also shared the analysis code so that the study can be reproduced.